'John Magnier doesn't miss a thing' – a rare interview with the staff who make Coolmore run like clockwork

Martin Stevens speaks to Paul and Joe Gleeson, Paraic Dolan, Martin Fogarty and Eva Haller in Good Morning Bloodstock

Good Morning Bloodstock is an exclusive daily email sent by the Racing Post bloodstock team and published here as a free sample.

On this occasion, Martin Stevens chats to Paul and Joe Gleeson, Paraic Dolan, Martin Fogarty and Eva Haller about their 180 years of experience at Coolmore – subscribers can get more great insight every Monday to Friday.

All you need do is click on the link above, sign up and then read at your leisure each weekday morning from 7am.

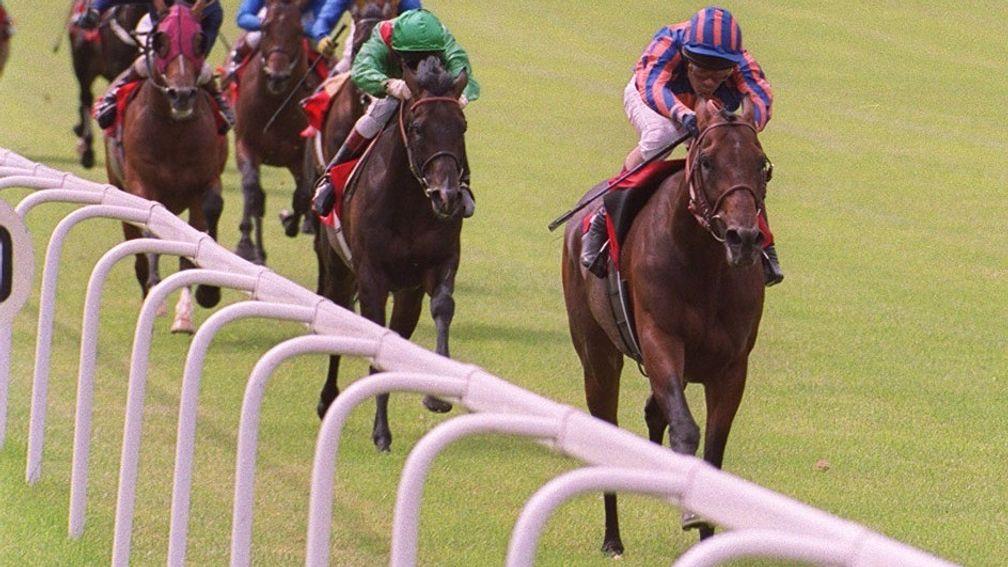

Breeding is an inexact science, but Coolmore sure have made it look as though they have it cracked with their stallion retirements this year.

City Of Troy, Auguste Rodin and Henry Longfellow are all homebred top-flight winners by internationally renowned sires in Justify, Deep Impact and Dubawi, and are out of Group 1-winning daughters of the operation’s late linchpin sire Galileo in Together Forever, Rhododendron and Minding – the dams being successful in consecutive renewals of the Fillies’ Mile, in an odd coincidence.

I was fortunate enough to see the three new recruits in their luxurious new home recently, but instead of recounting their pedigrees and racing achievements for the umpteenth time, I thought I’d get the word from as close to the horse’s mouth as you can get, by speaking to some of Coolmore’s employees on the ground over lunch.

Brothers Paul and Joe Gleeson, Paraic Dolan, Martin Fogarty and Eva Haller have a combined 180 years’ experience working on the stud, ensuring that it functions with almost mechanical precision: foaling mares, rearing young stock, breaking in the homebred and purchased yearlings, sending them to Ballydoyle and later welcoming a handful of the highest-achieving colts and most of the blueblooded mares back to the farm to start the process all over again.

Paul Gleeson is the longest-serving of the five, having worked in the stallion yard since 1980, when the foundations of the stud’s current dominance were being built. Vincent O’Brien and Tim Vigors were still key figures in the farm’s management in those days.

“We lived nearby and our parents worked on the farm, so I’d do a few jobs here at the weekends and during holidays, and then I came to work here full-time straight from school,” he says. “Noel Reddy and Eamon Phelan were managing the place at the time and then John Magnier took over.”

Asked if he can remember the first stallions he looked after, he puffs his cheeks and blows in an attempt to mentally sift through the hundreds he has had in his care, many from similar sire-lines – Northern Dancer, Sadler’s Wells, Galileo, Mr Prospector, Storm Cat, Danzig, Danehill and so on.

“Be My Guest was the big one, I suppose, and then there was a lot of fuss when Kings Lake and Golden Fleece came here,” he says. “Lomond arrived in 1983, not long after Thatch died. Thatch was one of a few Forlis we had for a while, so many in fact that part of the stallion yard was known as Forli Corner.”

It’s a similar tale for Joe Gleeson, although he travelled for a few years before returning to work full-time at Coolmore in 1990. His official role is stallion bookings, but his activities change throughout the year, along with the requirements of breeding and rearing horses.

“I’d be in the covering shed during the breeding season and then breaking in the homebreds for Ballydoyle in the off-season,” he says. “I’d be working with the yearlings from August to the end of November, and then go back to the stallions for two or three months before the breeding season starts again.”

Specifically, Gleeson oversees the yearlings in Walsh’s Yard, a hallowed space in which the cream of Coolmore’s homebred colts – those with the best pedigrees, best physiques and best grades as youngsters – are reared. City Of Troy, Auguste Rodin and Henry Longfellow are all graduates.

“Things were really taking off by the time I came back, as Sadler’s Wells became champion sire for the first time that year – Paul had done all the hard work as usual, he’d say,” he continues. “But it was a season a few years later that really sticks in the memory. It was 1998, the year that we broke in Giant’s Causeway, and we had about ten colts in Walsh’s Yard who went on to become stallions.

“Giant’s Causeway was the toughest yearling I ever broke. For about six weeks in a row, every day was like starting off all over again with him. He’d drag you around the yard every time you’d try to drive him. We got there eventually with him, but you can see how he was so hard on the track.”

County Monaghan native Dolan went down to Coolmore in 1986 straight out of school, and is another who has stayed there ever since. He serves as an area manager on paper, but is an all-rounder in practice.

“It’s a varied role,” he says. “I work very closely with Joe during the breeding season, booking in the mares, and I take care of most of the foaling units, so I get to see the newborns every day in the foaling season. I also deal a lot with people on the farm, with staffing issues and so on.

“Sadler’s Wells had his first crop of foals and Caerleon had his first crop of yearlings when I arrived. Law Society had recently retired and was, ahem, proving a bit of a handful. Coolmore has changed a lot, as it’s so much bigger now, but in another sense it's not changed at all really; the care and attention to detail with the horses is exactly the same.”

Fogarty, who arrived at Coolmore a little after Paul Gleeson, works with other homebred yearlings, mainly at the Barrettstown and Holloways yards. Two of the many top fillies he has had through his hands are Found and Minding.

“When I started at Coolmore it was just the top barn and the lower barn, and the cottage was under construction,” he says. “Back then I think there were around 35 staff dealing with the horses, and now there are too many to keep count of, as it includes seasonal staff. It was all about the Northern Dancers in those days of course, and Northfields had recently been bought for big money.”

Almost as jaw-dropping as the combined length of those old-timers’ service at Coolmore is the total value of the horses they have handled. When you think of all the high-earning stallions, golden-goose broodmares, blue-chip youngsters and expensive sales purchases, it must run into billions. Sadler’s Wells and Galileo on their own were priceless commodities at their peak.

None of the men have ever felt daunted by what the horses are worth, though.

“The first yearlings I broke at Coolmore had come from Kentucky, and they cost about three million dollars each on average, with some individuals worth as much as eight million,” says Joe Gleeson. “If you worried about the values you’d never be able to do your job properly. You soon get used to it.”

“You wouldn’t be able to get through the day if you thought like that,” agrees Dolan. “You’d never take the horses outside their stables, you’d be afraid of your life if anything happened to them. You just have to get on with it and give them the same standard of care you would any other horse.”

So Paul Gleeson, who looks after the stallions, doesn’t sleep with one eye open panicking about what City Of Troy or Wootton Bassett might be doing?

“Oh, you’re very much aware of their welfare all the time, that’s our number one priority, but there are plenty of other people looking after them too, and there's all sorts of security in place, so there’s no need to worry,” he says. “They are horses at the end of the day, you have to deal with them, and they don’t know what they’re worth.”

German-born Haller, who is a relative newcomer having had her first taste of working at Coolmore only at the end of the last millennium, and comes from a different culture, admits to having a few qualms in her early days, though.

“I came to Coolmore in 1999 to improve my English, on the recommendation of our German representative Michael Andree,” she says. “I went back to college after a year of being here and came back in 2008, and started running a yard.

“I went on to do yearlings, and then went up to Walsh’s Yard to work with the homebred colts, and I’ve been there ever since. From January to August I’m working in the office in registrations, so my year is split in two. I've improved my English as intended all those years ago, but not in the way I thought, as I’ve had to learn the Tipperary accent.

“To be honest, I was a little intimidated by the value of the horses when I first came here, as our horses in Germany wouldn’t be worth nearly as much money. I remember working with the boss’s mares and looking at the foals and thinking how much they’re worth, and it was frightening. But you soon get over it, all the horses have to be treated the same.”

With so much experience of dealing with good horses, did the Coolmore team on the stud therefore know that the young City Of Troy, Auguste Rodin and Henry Longfellow would turn out to be superstars and stallion material?

“Well, they were in Walsh’s Yard for a reason,” says Dolan. “Anything that’s in there is among the best 15 to 20 homebred colts we have, on paper at least.”

“But you’d be only guessing at that age, in my opinion,” says Fogarty. “We’ve had 29 individual Group 1 winners come out of Holloways, where we keep the fillies, and I picked out only one as a champion, and that was Happily.”

Joe Gleeson says: “I think the differences start appearing when you’re lunging. By the second week, when they’re used to it, some would be lunging way better than the others, but that doesn’t mean they’re going to be way better at racing.”

“It probably gives a more accurate indication of their mind and willingness, than their ability,” nods Haller. “You can always tell the ones who want to do it.”

City Of Troy, who blends the raw power of Justify with the Classic refinement of Galileo, was foaled in Kentucky but reportedly started receiving high ratings as soon as he arrived in Fethard.

“He was always in the top ten of the yearling colts in Walsh’s Yard,” says Dolan. “Perhaps he was a little light-framed and narrow in those early days, even a bit nervous sometimes, but he was the exact opposite of that when he went racing, he just took to it. He has Galileo’s mental attitude, he reminds me of him a lot actually.”

Haller meanwhile had her head turned by the sleek, elegant, dark frame of Auguste Rodin as soon as he arrived in Walsh’s Yard. Everyone liked him, but she was “ranting and raving about him” according to her colleagues.

“Yeah, I liked him from day one,” she says. “I said to anyone who would listen that they had to look at him and take him seriously. There was just something so different about him. I’d never seen anything like him before – not just his colouring, but the way he moved and his whole attitude.

“He was always so keen to do everything correctly. It was incredibly impressive. I wasn’t at all surprised when he won all those Group 1s.”

As for Henry Longfellow, Joe Gleeson says: “Ah, we all loved Henry. We had three Dubawis in Walsh’s Yard that year and there wasn’t much to distinguish between them, they were all similar in looks and attitude. They’re very willing.”

Breeding and rearing well bred colts and getting them to win big races to justify bringing them home to stand as stallions isn’t always as easy as Coolmore have made it look this year, though.

“If they don’t make it, you tend not to remember them,” Gleeson confesses. “We’ve had some really good-looking yearlings who didn’t even run, let alone win, and I couldn’t tell you their names or pedigrees now. When they leave the yard, you make a note of the ones you liked, but sometimes you never hear of them again.”

“You always make sure to let us know when you did pick one out as a champion though,” Dolan interjects with a laugh.

Dolan goes on to nominate Accordion, a half-brother to Derby runner-up Hawaiian Sound from the first crop of Sadler’s Wells, as a prime example of a yearling who received top marks and was expected to take the world by storm, but never made it to the track, to a wave of nods from the veterans around the table.

“He was just a magnificent foal and became the most absolutely stunning horse you’ve ever seen, but he had a hole in his heart so couldn’t run, and that was that,” he says with palpable disappointment even 38 years later.

Accordion did at least find redemption as an accomplished National Hunt sire, his roll of honour headed by Accordion Etoile, Albertas Run, Dato Star, Feathard Lady and Flagship Uberalles.

What about a horse who defied expectations? One who hadn’t received the highest marks from Coolmore stud staff but found fame on the track?

“The grading gives you a fair idea of how well they’ll do – Henri Matisse and Twain were highly thought of in the 2023 intake, for example, and they've followed through as well – but I suppose one who wasn’t estimated to be as good as he turned out to be was Saxon Warrior; he surprised us,” says Dolan.

Joe Gleeson adds: “Mastercraftsman was a brilliant racehorse who didn’t show us an awful lot. He was a plain grey with big feet, I didn’t think much of him.”

You won’t be surprised to learn that Galileo was the model pupil in Walsh’s Yard, and that most of his sons who followed him there were equally as attractive and amenable.

“Harry [King, Coolmore’s long-serving farm manager] always talks about the young Galileo,” says Dolan. “He says he was streets ahead of anything else on the farm that year. He was just different, somehow.”

“I remember when he came home as Sadler’s Wells’ first Derby winner, he was very special,” says Paul Gleeson.

Dolan agrees, adding: “You know, it always sticks in my mind when he arrived after the Breeders’ Cup and his hind legs were so sore from the dirt burning him. He had been skidding on it, it tore the hair off the back of his legs.”

He admits candidly that he “didn’t particularly like” Galileo’s first crop of foals, but quickly came round to the sire’s stock when they started to show their class.

“We were spoilt for a long time because we had his progeny for so many years,” says Haller. “All they wanted to do was please you. They were just very genuine and very quiet, you could do anything with them.”

“The thing about Galileo was he was as quiet as a lamb, and so were a lot of his stock, but they were tough as nails deep down,” says Dolan shaking his head in disbelief. “Jeez he was a tough horse. He should have died when he had colic that time, but he came through it.”

“Sadler’s Wells was the same,” says Joe Gleeson, with the table growing more animated as anecdotes about the era-defining father and son are shared.

“So easy to do,” agrees Paul Gleeson. “Lovely, placid horses.”

“Sadler’s had his moments though,” replies his brother. “I remember when I was walking him, if there was a bucket on the avenue that hadn’t been there the day before he wouldn’t go past it, he’d start going backwards. He was a bit strange like that, he liked his routine.

“When I was giving Galileo exercise in his later years I’d give him two laps before he could go down for a graze in his paddock. He was always as quiet as a mouse on the first lap but he’d drag you back on the second lap because he knew it was time for his graze. He was clever, he knew what was going on.”

“Yeah I suppose Galileo had a few funny little habits, like pulling straw up to the stable door so he could rest his head on it,” says Paul as he thinks about it a little more. “Some of his sons do the exact same thing, it’s uncanny.

“Sadler’s Wells was a dream in every sense though. He’d go into the covering shed and he’d do his job, and then he'd return to his box and lie down and go to sleep.”

Sadler’s Wells is particularly close to the hearts of the older brigade at Coolmore, unsurprisingly when he was the horse who made the farm.

“He was the highest-priced horse we’d ever stood at that stage, at Ir£125,000,” continues Gleeson. “He was exceptional. He proved that straight away, when his first-crop sons Prince Of Dance and Scenic dead-heated in the Dewhurst.”

Mention of Scenic prompts an amusing aside from Dolan.

“We ended up standing him – now there was a lunatic,” he mutters. “Talk about a box-walker; he wouldn’t so much walk around the box as run around it. That wasn’t Sadler’s, though, that must have come from the dam’s side.”

“The Sadler’s Wells’ and the Galileos were nearly always a joy to break in, though,” says Joe Gleeson, getting back to the matter at hand. “You could ride them two days after starting work on them.”

Coolmore doesn’t tend to do displays of emotion, but the top brass relaxed their stiff upper lip when Sadler’s Wells died at the age of 30 in April 2011.

“All the staff were called to come in and say our goodbyes to him when he passed away,” remembers Paul Gleeson. “The whole place was gathered in his paddock as he was put to sleep. A lot of the people who had been there the day he arrived were also there the day he died.

“There were a few tears shed that day, but then he’d been there for so long, and had been such a huge factor in the rise of Coolmore.”

Of course, the stud’s stallion boxes were graced by another exceptionally gifted son of Sadler’s Wells in the new millennium, in Montjeu. He was renowned as a superb source of stamina, but also for imparting a little artistic temperament, to put it kindly.

The staff who dealt with him and his progeny acknowledge that he might not have been Peter Perfect like his paternal half-brother Galileo, but suggest that his idiosyncrasies might have been exaggerated a little over the years.

“Sure, temperament-wise Montjeu was fine,” says Paul Gleeson. “But he could be quirky, like. You could bring him out some mornings and he’d just stroll along, and then other days he’d be up on his hind legs the whole time. But there was no badness in him at all. Now, having said that, his daughters can be tough in the covering shed.”

And what about Montjeu's yearlings?

“I liked his stock as soon as I saw them but, oh my God, breaking in the colts wasn’t easy,” says Joe Gleeson.

“You wouldn’t necessarily trust them, either,” adds Haller.

Gleeson agrees, but adds: “Look, Galileo and Sadler’s Wells were very rare, most other sires are somewhere on the quirky spectrum. The Storm Cats and War Fronts were also hard to deal with, and the Danehills could be tough too, but you have to remember it can come from the dam’s side as well.

“We had some trouble breaking in a colt by Frankel last year. His yearlings are usually incredibly quiet, so it most probably came from the dam. Sometimes that attitude goes hand in hand with ability, too, so it’s not always a bad thing.”

Dolan, Montjeu’s number one fan at the table, says: “He was probably the best racehorse who ever stood at Coolmore. He didn’t always put that temperament into his foals. Camelot didn’t have it when we broke him in, he was straightforward. He developed a few quirks later on, and his yearlings can be a little quirky too, but not badly at all.

“Camelot had a fantastic year in 2024 with the likes of Bluestocking, Luxembourg and Los Angeles, and I know there are some more nice horses by him in Ballydoyle. When he gets a good one, he gets a really good one.”

“Camelot’s a gas,” says Paul Gleeson, who works closest to the horse. “You can take him to the lunging ring, and he’ll just stroll around, he won’t lunge for you at all. But put him back in his paddock and he’ll start flying around like a kite.”

Dolan says: “To be honest, we’ve never had many stallions at Coolmore who aren’t easy to work with. Caerleon and Law Society were maybe the hardest to manage. Montjeu wasn’t in that category at all, he was just flighty.

“John Hammond said when he was training the horse he’d bring him out into the yard and try to get him to turn left, but he wouldn’t, so he learned that the best thing to do when he wanted him to turn left was to ask him to turn right instead. Then he’d turn left.”

Conversely, the Coolmore stud staff describe Galileo’s successor at the top of the Coolmore roster, Wootton Bassett, as “a true professional”.

“Ah he’s grand,” says Paul Gleeson. “I wasn’t sure what to expect when he came off the lorry a few years ago but he’s a lovely, strapping horse with a proper stallion’s head on him. Mind you, he can be a bit hyper in the breeding season. There’s no badness in him but once he sees a mare, he wants only one thing.”

“Yeah he’ll take you up the road to the covering shed rather than vice versa,” agrees his brother. “He knows his own way there. But he’s very good once he gets in there, in fairness.”

Better for the team that he’s a Don Juan than a damp squib. The long-servers have bitter memories of a former resident who was a great racehorse but frustratingly gun-shy in his second career.

“Dr Devious would stand there looking at everything bar the mare and there was nothing you could do about it,” says Dolan.

“We tried everything,” adds Joe Gleeson. “One evening in the covering shed we let him and the mare loose, turned off all the lights and gave them five minutes. When we turned the lights back on, there was the mare walking out behind Dr Devious. We just took him back to his box, there was no point.”

Back to Wootton Bassett, Haller pays him the ultimate compliment by saying: “His yearlings are professional too. They’re no trouble at all. In fact, I’d say they’re the closest thing to the Galileos I’ve seen in terms of attitude.”

Joe Gleeson agrees, and adds: “The big thing about Coolmore is the homebreds have a head collar on from the moment they hit the ground, and they’re handled every day, so they should be quiet, to be honest.

“It can be tougher when you bring one in from somewhere else, as they might not have had the same handling. The stud that had them before might let their foals run loose, they might not have the staff to give them the same treatment. But they all settle down eventually.”

And what does the team think of Coolmore’s other big-hitter, Justify? They might not know the horse himself all that well, as he stands at Ashford Stud in Kentucky, but they will be well acquainted with his yearlings by now.

“They’re very tall, like their father,” says Fogarty. “Some of them have massive frames.”

“City Of Troy is a big horse,” adds Paul Gleeson, which provokes a flurry of jokes about the silly storm in a teacup over his stature last year.

“He’s 16.1 on the stick,” he declares with authority, putting the issue to bed once and for all.

He is soon distracted by mention across the table that Justify weighs 700 kilos, though.

“What, 700 kilos?” he says with an audible gasp. “I’ve never seen one weigh that much. Most of ours would average around 560 and 580 kilos. Australia is about 630 kilos, but he’s lazy, Wootton Bassett is about 600 kilos and Camelot is about 590 kilos.”

“Yeah, because he won’t lunge!” pipes up Dolan.

“I think Fastnet Rock was our heaviest ever, at about 640 kilos,” continues Gleeson as he shakes his head. “We’ve never had one over 650. Justify must be a monster!”

City Of Troy, Auguste Rodin and Henry Longfellow have settled into Coolmore “grand” he reports. “All three seem to have good temperaments. It’s a rare thing to do, to get back three well bred colts who were reared on the place.”

Now it’s over to his brother, with the assistance of Dolan, to organise all the coverings the newcomers and their colleagues have to complete between this week and midsummer.

Trying to fit mares into a busy stallion’s schedule is like air traffic control at Heathrow Airport. But instead of keeping planes waiting to land in the air until another has taken off, they are juggling veterinary reports and slots in the shed.

“We’ve been at it so long now that we know most of the clients inside out, and they know us, so even if we tell them they’ll have to ring back and check again tomorrow, they know we’re trying our best,” says Dolan. “It’s very rare that we don’t get a mare covered when they want.”

Joe Gleeson says: “It’s spinning plates most of the time. For example, some people won’t be able to get a vet until 4pm in the afternoon, at which point we’ve got all our slots allocated for the day, and they’ll say ‘gee, the mare might not last until the morning, can you swap something around’, and then we’ll have to ring the person who had the last slot of the day to see if they can push on to the next morning.

“It can sometimes take seven or eight phone calls over an hour, with each party then having to ring their vets, to get things sorted. That can be hard work.

“A busy stallion would typically cover at 6am, at noon, in the afternoon and at night. The most important thing is to fill that first slot in the morning, to have the flexibility to do three or four covers over the rest of the day if need be. If the morning slot is free, but there are two phone calls coming in for the same time later on, we’d get one over as quickly as possible to cover there and then.”

Dolan adds: “We had a good one last year. A mare owned by an elderly couple didn’t turn up for the first-slot cover, even though the husband had been ringing us every day for ten days to tell us the follicle size.

"We rang them up and the wife said she’d lost her footing while loading the mare in the pitch black and the mare had got loose, and they hadn’t found her yet.

“It’s not unheard of that someone will ring up at 5am to say their box has broken down either. If they’re close by, we’ll always do our best to help them out.”

The rest of the table are looking quietly relieved that they don’t have to participate in that particular administrative nightmare.

“I don’t get involved,” Paul Gleeson says with a little too much relish. “I just get the covering sheet and make sure the stallions cover the mares as they arrive. All I need to do is make sure they’re the right horses, as you don’t want to mix up a €10,000 horse with a €200,000 horse, but happily the microchip has taken the peril out of that. We’ll double check markings too, though, especially for walk-ins.”

Haller can empathise with Joe Gleeson and Dolan, as she spends half of the year in registrations – “anything that needs to be written down, basically: foalings, veterinary records, all communications,” she says.

Considering Coolmore houses more than 500 mares foaling each year, between the stud itself and its clients, her in-tray at this time of year is always overflowing.

Fogarty has been assiduously keeping his head down during this discussion.

“My life is pretty admin-free,” he eventually admits sheepishly.

Cue uproarious laughter from his colleagues. “What a life!”, “Sounds idyllic”, “He’s 80 years of age really,” are among the more printable comments.

“It’s true, I suppose, the horses are easy enough to deal with, as long as they’re not sick, but people can be harder to manage,” he says. “There’s a good few of us there covering a big area, but there’s often someone off with illness.”

There ensues a discussion about standards of staffing nowadays, which involves a fair bit of grumbling about young people being glued to their mobile phones.

“I actually see an improvement in the younger generations coming through recently,” says Dolan. “It can be a hard job, in the breeding season it’s round the clock, you don’t get much of a day off, the phone can ring at any moment, but you do get to breathe out in the off-season. It’s also a very healthy career, and a great way to see the world.”

Haller, the youngest team member in the room, can see why stud work might put off some people who want to maintain a modicum of a social life.

“But it depends on how much you want to involve yourself,” she says. “You can work here and treat it as a normal job, and do your own thing, but if you really want to do well, you need to be always thinking about the horses, and be ready for anything and always be contactable.

“Personally, I always wanted to throw myself into the job completely.”

Dolan sums up: “In fairness, none of us would have been here as long as we have been, and raised families here, if it wasn’t a good career."

You couldn’t ask for more job satisfaction than seeing homebreds like City Of Troy, Auguste Rodin and Henry Longfellow come back to the farm as stallions. The horses crop up when the Coolmore team members are asked for their most enjoyable moments in their time on the stud.

“I’d have to say backing Minding to win the Fillies’ Mile at 20-1,” says Fogarty. “She ended up winning at 5-4 and I was at Newmarket to see it. She was probably one of the best mares we’ve produced, so it was nice to have her back, and then to get Henry Longfellow out of her. She’s definitely a favourite of mine.”

“Auguste Rodin winning the Derby for me, especially as he was coming back from that disappointment in the 2,000 Guineas,” says Dolan, not very gallantly when he knows that the horse is Haller’s pride and joy.

“I was going to say that,” she protests. “I suppose instead I’d say Saxon Warrior winning first time out at a big price, as he was one of the first yearlings I worked with. He was another Deep Impact, but totally different to Auguste Rodin in looks.”

Joe Gleeson's favourite time was his first trip to Royal Ascot, which came not long after Covid.

“I’d never been before, I'd seen it only on television, but most of the staff went for the day," he says. "It was a rare day when Ballydoyle didn’t have a winner but I didn’t mind as we all had a great time anyway.”

It could be about only two horses for his brother.

“I’d have to go with Galileo winning the Derby," says Paul. "Sadler’s Wells was 20, and he’d been hitting the crossbar with seconds and thirds until that point. It was the way he won as well; he was in a different league. Sadler’s Wells is probably the closest horse to my heart, as he started it all, but Galileo is up there too.”

Finally, what do they think has got Coolmore to this point, where all the constituent parts of its machinery are working in perfect harmony to produce three homegrown stallion prospects in one year? The question is intended to elicit five different responses, but there is only one answer.

“That’s very simple,” says Dolan to a chorus of approval around the table. “It’s one thing, and that’s John Magnier. It’s his attention to detail.

“He’s still very hands-on. He reads the covering sheet every morning during the season, and he’ll want to know why one client’s mare is being covered before another client’s mare. ‘Do you know how much business that man does with me?’ he asked once, and I said, ‘Ah, I know, but we're in a bind and his mare's vets aren’t wonderful.'

“'Well, I hope you’re right,’ he said. When the guy who’d been shuffled back called the next day looking for his cover, the boss just said, ‘You got lucky. I like that’.”

Nodding, Joe Gleeson says: “He’s across everything. If I have to send him something I'll read through it 50 times before I do, because he’ll find something no-one else would. He doesn’t miss. He just does not miss. He set those standards 50 years ago, and has never dropped them.

“In my first couple of years at Coolmore, when you bumped into him on the way to the covering shed with a mare, he’d stop you and ask whether the mare had a foal, and who the foal was by, so I’d get into the habit of memorising the door card before I left, just in case he asked.”

“Ah stop,” says Dolan. “I remember in my early days here he’d come out during the evening cover in the breeding season and ask about the mare. One day he asked and I did my best, telling him the name, the identity of her owners and the sire of her foal. ‘This is great,’ I thought to myself, ‘I’ve passed the test’.

“Then he asked what the foal weighed when he was born. I had no idea but I’d seen foal weights on other mares’ door cards so I went in with what I thought was the average: 118lb. ‘Oh, very good,’ he said, and went off. Phew.

“Then he stopped in his tracks and turned around and said: ‘And what was the afterbirth weight of that foal?’

"I took a swing and said 15lb. He thought about it for a bit, and replied, 'Hmm. That is impressive. It’s amazing you knew all that, because the foal wasn’t even born here’, and then carried on walking. There's no point trying to pull the wool over his eyes. You can't fool him.”

Magnier might sound like a hard taskmaster but it is clear from the warmth with which his employees speak about him that he inspires respect rather than instils fear.

The feeling must surely be mutual, with the boss holding the long-serving staff who have helped Coolmore become the slickest breeding operation in the world in high regard.

That has to be the case really, as those three homebred new stallions, all out of Group 1-winning mares (sorry to labour the point, but it really is an astonishing feat when you think about it) could never be the product of chaos and acrimony.

Refer a friend!

If you have a friend who would like to receive Good Morning Bloodstock please send the following link where they can sign up.

What do you think?

Share your thoughts with other Good Morning Bloodstock readers by emailing gmb@racingpost.com

Must-read story

This story is exclusive to Ultimate Members' Club subscribers. Sign up here to get unlimited access to our premium stories.

“Willy's hungry, he knows exactly what he wants to do, the little things he likes to do and Dad doesn't so much, which is why they're so good together,” says Sam Twiston-Davies as he gives an insight into life at Grange Hill Farm in a wide-ranging interview with Peter Thomas.

Pedigree pick

It’s Britain v Ireland in a trappy fillies and mares’ bumper at Ayr on Tuesday (4.55), with three well credentialled horses from each side of the Irish Sea facing off against each other.

Stuart Crawford’s newcomer Royal Hillsborough, a Conduit half-sister to classy chaser Perfect Candidate, makes plenty of appeal on paper, but preference is for Nicky Richards’ Carlisle bumper runner-up Gintime, whose pedigree is tailor-made for the task at hand.

The five-year-old is by Mount Nelson, on the mark with Saturday’s Newbury Listed bumper winner Sober Glory, and is the first foal out of Tramore bumper winner Irish Lass, a Getaway half-sister to Airlie Beach, who won her first seven starts, a run that started in a Kilbeggan bumper and culminated in the Grade 1 Royal Bond Novice Hurdle.

Remarkably, Irish Lass and Airlie Beach are siblings to five other bumper winners, in Ain’t No Sunshine, Dr Machini, My Trump Card, Screaming Rose and Valerian Bridge.

Don’t miss ANZ Bloodstock News

Subscribe for the latest bloodstock news from Australia, New Zealand and beyond.

Good Morning Bloodstock is among our Racing Post+ offering. Read more Racing Post+ stories here:

'He's the most exciting horse we've had at this stage of his career - and he's in great shape'

'He's an absolute dude' - behind the scenes with chasing superstar Galopin Des Champs

Wathnan Racing snap up classy King's Gambit before run in $2.5m Group 3

Good Morning Bloodstock is our unmissable email newsletter. Leading bloodstock journalist Martin Stevens provides his take and insight on the biggest stories every morning from Monday to Friday.

Published on inGood Morning Bloodstock

Last updated

- 'It's a fresh chapter' - Highclere Stud diversifies but blue-chip breeding remains its raison d'etre

- ‘She just wasn’t normal’ – recalling a tiny but top-class filly back in the big time as dam of a champion

- 'The word is definitely out about him' – meet the new stallion whose good looks have set tongues wagging

- 'I'm told we got the best young sire in France' – an update from the rising force that is Capital Stud

- 'I sealed the deal for Sir Gino in McDonald's' - catching up with French-based talent scout Toby Jones

- 'It's a fresh chapter' - Highclere Stud diversifies but blue-chip breeding remains its raison d'etre

- ‘She just wasn’t normal’ – recalling a tiny but top-class filly back in the big time as dam of a champion

- 'The word is definitely out about him' – meet the new stallion whose good looks have set tongues wagging

- 'I'm told we got the best young sire in France' – an update from the rising force that is Capital Stud

- 'I sealed the deal for Sir Gino in McDonald's' - catching up with French-based talent scout Toby Jones